Rescue Me

Damon Smith on Bringing Out the Dead

“Life does not cease to be funny when people die any more than it ceases to be serious when people laugh." — George Bernard Shaw

Of the very few Martin Scorsese films we might call underloved, Bringing Out the Dead, his exhilarating street-savior odyssey, is arguably the most fraught. Despite a handful of favorable-to-ecstatic reviews from major critics, Dead was a box-office failure in 1999 and has labored for visibility ever since, though it's widely available on DVD. Nevertheless, appreciations continue to surface as critics and fans—including French director Bertrand Tavernier—take another look. Even the filmmakers have taken up the cause. In a recent interview for The Wolf of Wall Street, Scorsese’s longtime editor Thelma Schoonmaker stated that Dead flopped commercially because it was "poorly marketed" and asserted that it's "the one we’re waiting to be recognized.” Producer Scott Rudin, reflecting on his tenure with Scorsese in the same piece, thoughtfully likened their portrait of a spiritually distressed, nerve-wracked New York City paramedic to "an American Pasolini film."

So where's the disconnect?

Perhaps it's a question of genre. Many reviewers initially hailed the film as a gritty urban parable exploring guilt and responsibility in a brute-realist quasi-religious framework, a characterization that stuck. (“Blunt, truthful, uncompromising,” marveled Richard Schickel for Time. “It’s hard on an audience, even harrowing.”) Other writers, buying this solemn appraisal, found the story and performances unconvincing but praised the film’s bold visual artistry and rollicking, caffeine-fueled set pieces in the ambulance. For today's enthusiasts, Dead sits comfortably alongside rough-and-tumble character studies like Mean Streets or Taxi Driver (misfit heroes fighting their demons, exoticized views of sordid city life, passenger-seat jive), while more distantly echoing the introspective personal journey of Kundun, which immediately preceded it. Still the film remains an outlier, ignored by programmers of two recent Scorsese retrospectives in New York and the public alike. Clearly, Bringing Out the Dead does not need to be rescued from oblivion; it needs to be resuscitated. Let's start by calling it a comedy.

I would argue that Dead will be slow to claim “classic” status unless we develop a fuller appreciation of its outlandish gallows humor, as well as its caustic mix of sacred and profane sensibilities—a Scorsese specialty. The director’s penchant for black comedy runs through much of his dramatic work (beginning with the “Watusi” sequence in Who's That Knocking at My Door), transmuting moments of danger and tension in Goodfellas, Casino, and Gangs of New York into bloody jocularity. Sometimes, as with The Wolf of Wall Street, it is the primary tone for all the bad stuff that happens. Alongside The King of Comedy, Scorsese's antiheroic fable of delusional ambition, Bringing Out the Dead is one of the darkest, funniest movies in his oeuvre.

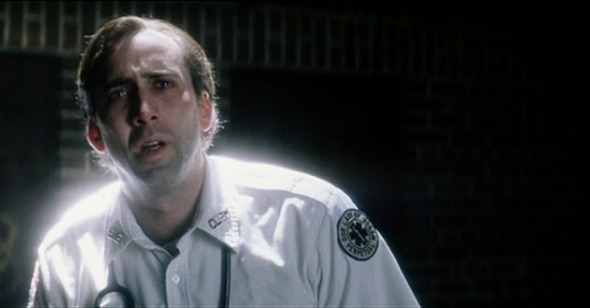

Adapted from a novel by Joseph Connelly, a former EMT, Bringing Out the Dead reunited Scorsese with screenwriter Paul Schrader (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, The Last Temptation of Christ) after a ten-year creative divorce. Although much of the film's gravitas and voiceover narration are borrowed from the source material, Scorsese's driver's-seat execution and hectic pacing is intense, flashy, and stylistically engineered for grim laughs, punctuated here and there by assault-and-battery melds of rock music (The Clash, Johnny Thunders, R.E.M.) and time-lapse travel shots captured in multiple low- and high-angle camera placements. Set in pre-Giuliani Manhattan “in the early 90s,” as the opening titles pointedly clarify, the film trails Frank Pierce (Nicholas Cage)—a sleepless, burnt-out paramedic toiling on the graveyard shift in a modern Gomorrah of lost souls and burnouts. Haunted by the memory of Rose (Cynthia Roman), an 18-year-old homeless girl he failed to save six months before, Frank is an emotional and spiritual basket case brooding constantly over the suffering masses he’s charged with helping. “I hadn’t saved anyone in months,” he tells us in Cage's wearied monotone. “I just needed a few slow nights, a week without tragedy and a couple of days off.”

Needless to say, he gets none of the above over a long, eventful weekend—especially sleep. (His insomnia recalls De Niro’s taxi driver’s lament: “Twelve hours of driving a cab and I still can’t sleep.”) Frank's partners on the night watch are a revolving door of dysfunctional kooks whose incongruous attitudes toward misery act as a foil for Frank’s weight-of-the-world heavy-heartedness. First to arrive is the affable, overweight Larry (John Goodman), who's more preoccupied with food and the strenuous nature of 911 call response (“Why is it always the top floor?”) than he is the life-or-death contingencies of his work. Next comes Marcus (Ving Rhames, siphoning some of Little Richard's performative juju), a cigar-chomping born-again Christian who gets off on the adrenaline rush of saving lives when he isn't cruising hookers and sermonizing to Frank about his Rose problem. ("People who see shit are crazy.") Then there's Tom (Tom Sizemore), a wild-eyed sociopathic menace who likes to fuck with every one of his patients, especially the head cases and drunks. ("The war's over, Tom," Frank says dryly at one point, after the unhinged medic, having pummeled a loony, pops up excitedly to answer a double-gunshot-victim radio call.) Even Frank's captain (The Sopranos' Arthur J. Nascarella) seems slightly off-kilter, barking like a dog for declarative effect and promising to fire Frank if he'll just finish his weekend shift: “Go help the people of New York, do your job.”

Although it would be a stretch to call Bringing Out the Dead a conventional "comedy," there's a slapstick quality to Frank’s quest for rest and redemption that Scorsese is keen to emphasize with visual gags and punch lines. Sometimes the humor is black-hole black. (In one scene, Marcus joyously holds aloft a newborn twin he’s just delivered and asks Frank, “How’s yours?” Scorsese cuts acidly to a ceiling shot of Cage looking down at a bluish infant corpse). Every call from the dispatcher (voiced by Scorsese—another well-played joke) is torturous for Frank, who fears the next cardiac patient will soon lie dead in his hands. The medic’s only human connection is with Mary Burke (Patricia Arquette, bringing her signature mix of virginal coquettishness and mysterious vacancy), a former drug addict whose father lies comatose in a vegetative state after Frank managed to reboot his heart with a last-chance electric shock—and a little Sinatra. At the hospital, Frank gives her cigarettes and zombified pep talks in the parking lot as he listens to her bemoan the crushing pressures of life in the concrete jungle. The couple’s interactions are awkward and emotionally flat ("Do you want to fuck me? Everyone else has"), perhaps not always intentionally, but the sweetly morose, his-and-hearse dynamic is funny nevertheless.

Working hard to soften his recently honed Con Air bravado, Cage reaches for the kind of human depth he mined as a suicidal screenwriter in Leaving Las Vegas, reminding us how great he can be in unconventional roles. Gaunt, stricken, and soul-bruised, Cage’s Frank is constantly on the verge of either cracking up or breaking down. He walks and talks like a catatonic combat veteran through most of the film, reminding everyone “I’m sick, I don’t feel so hot,” even shooting a vitamin B cocktail intravenously with a coffee chaser when he needs a pick-me-up. The contrast between Cage’s slumped body language and his hair-trigger improvisational flourishes with Rhames and Sizemore—a host of crazed grins and sarcastic outbursts—is what give his chronically exhausted character such humorous volatility. By the time he ventures into the Oasis, a luxurious reggae-vibe “retreat” where drug lord Cy (Cliff Curtis) provides medicated respite from the noise and pain of the city, Scorsese and Cage have conspired to turn Frank—now over-the-top ghoulishly pale—into Lon Chaney. His howling “paradoxical reaction” to the Red Lion pills Cy gives him (keyed to the Japanese-themed doo-wop of the Cellos’ “Rang Tang Ding Dong”) unleashes one of Scorsese’s most elaborate fantasy sequences, as outstretched arms emerge from manholes, too many souls for Frank to help or pull to safety.

In some ways Dead is closest in Scorsese’s filmography to After Hours—another late-night Manhattan odyssey where Griffin Dunne’s Paul Hackett crosses paths with an assortment of neighborhood nutters and artsy oddballs in mid-eighties Soho as he tries with farcical desperation to get home and go to bed. Setting Dead in the era before Mayor Rudy Giuliani swept the mentally ill and vagrant population from public view (“This city’ll kill you if you aren’t strong enough,” says Mary, voicing one of the truisms dear to New Yorkers, once upon a time), Scorsese seems nostalgic for Gotham’s then-recent past as a lost, untamed wilderness. And his witty feel for the urban grime and down-and-out heartbreak in Bringing Out the Dead’s reimagined Hell’s Kitchen is everywhere apparent. The ER lobby at Our Lady of Perpetual Mercy Hospital is a riotous throng of fighting families and hard-luck cases presided over by African-American security officer Griss (Afemo Omilami), a gruff type whose no-bullshit policy elicits a comically stern warning: “Don’t make me take off my sunglasses....” Inside the trauma unit, there is more bedlam. Moaning, bloodied patients are piled on gurneys in the hallways, frantic staff race to manage the influx of patients (or berate them in the case of Mary Beth Hurt’s arch intake nurse), and resident maniac Noel (a dreadlocked Marc Anthony, more convincingly crazy—and sympathetic—than you would expect) screams at everyone for water. It’s all dizzyingly funny, and true to the world of big-city trauma rooms.

A New York native with a geometer’s precise sense of location, Scorsese has a gift for neighborhood atmospherics (in the nighttime, especially), and the boroughs have always been the setting for his most triumphant outings; the city’s noise and ferment cling like static to the edges of characters like J.R. and Johnny Boy, Travis Bickle and Henry Hill. As a metropolitan tale, Bringing Out the Dead crackles with lunatic energy and Corman-esque shocks: Noel flinging his bloody Rasta locks into Frank’s face and randomly bashing cars with a baseball bat, Tom’s paramilitary zeal for “blood spilling in the streets,” a Filipino nun barking anti-sex-crusade lingo through a megaphone, the Orthodox Jewish tagalongs who bring their own spotlight to watch fire squads deal with potential jumpers. These are visions of excess, sensory overload, the mania of people packed too tightly in limited spaces. Scorsese captures all the madness and absurdity with bursts of technical bravura, occasionally mimicking the psychic agitations of his home turf with bum-rush swivels and zooms, gliding pans of street-level grotesquerie, lens twists, and snatches of overheard conversation (“Beat the shit out of him, baby!”).

In Frank’s eyes, the city is a nightmarish place of lonely desperation and dashed hopes, stillbirths and attempted suicides, anarchy and insanity—but more than anything of spirits begging for release. (The bluesy harmonica peals of Van Morrison’s “T.B. Sheets”—a song about a tubercular girl’s desire to escape the stifling death smell of her hospital room—is Dead’s downbeat leitmotif, heard repeatedly on the paramedics’ somber crawls through alleys of anguish.) Frank is a persecuted savior whose fraught efforts to relieve the world of pain are both humbling and, he admits, magnificently addictive ("Saving someone’s life is like falling in love, the best drug in the world. God passed through you...For a moment there, God was you"). True to the crusade, he ventures valiantly through a gauntlet of seedy milieus—a grungy basement, a packed underground rock club—that both mock and emblematize his haunted, unforgiving work routine. (“You’ll be going to the man who needs no introduction,” jeers the merciless radio dispatcher. “The duke of drunk, the king of stink, our most frequent flier, Mr. Oh!”) Scorsese frames Cage in close-up at one point, a despairing angel hugged by soft-focus colored lights and weeping reflected rainfall, an image worthy of Caravaggio. Drifting amid the lowly denizens of New York, Frank ministers to crackheads and gangbangers, hookers and homeless alcoholics with a tender ambivalence that rivals any holy man’s, including Scorsese and Schrader's vision of Christ.

No outsider to Galilean theology and its earthly paradoxes, Schrader packs his three-act screenplay with religious imagery and allusions to sin and penance, curses and miracles, ghosts and the Holy Ghost, angels and demons, heaven and hell, all gnarled in a coil of subtle (and not so subtle) thematic contrasts. Convents, priests, Madonnas, and virgin births round one side of the Christian double helix that is Dead’s DNA; drugs, violence, mayhem, and illness curve along the other. There are grace notes, too: One of the film’s most intimate scenes, and certainly the most affecting, is Frank’s final encounter in the ICU unit with Mary’s unconscious father (Cullen O. Johnson), who’s been badgering the medic on a subconscious wavelength to let him die. Somehow Cage, beneath raccoon eyes and a skull-mask of bereaved sympathy, channels all of Frank’s inner torment and fatigue to make a final act of compassion fully lucid, a feat of acting all the more potent for its silent restraint. In the film’s closing scene—a Sunday-morning bedroom pietà—Scorsese bathes the reclining Frank and Mary in a gradually dawning flare of celestial white light. Amen.

Without its madcap visual rhythms and deranged humor, Bringing Out the Dead would potentially flatline due to its headier aims as a salvation story. Horror and hilarity go hand in hand in this film (as Cy hangs precipitously skewered above the Manhattan skyline, his abdomen pierced by iron grating, he sniffs Frank's breath and inquires "Chinese food?"), allowing us irreverently dramatized glimpses of a pretty depressing line of work. Laughter is a salve for all the indignities of death, the film might be telling us, as well as the reward for contemplating its irreversibility. And the gamble Scorsese has taken with this material—setting off firecrackers in the morgue, as it were—pays off scene to scene. Frank’s disgust with a frail, Gollum-like depressive (“That’s the worst suicide attempt I’ve ever seen...You feel that pulse? That’s where you cut. And it’s not across, it’s down, like so”) is hysterically inappropriate. So is Marcus’s impromptu prayer circle to “resurrect” a white New Wave rocker improbably named I.B. Bangin’ (“I rebuke the spirit of drugs in the name of Jesus!”) while Frank furtively administers Narcan. Even the title of the film, mindfully preserved from Connelly's novel, is a cheeky nod to the Black Death corpse collector’s cry (“Bring out your dead!”) in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. But the last wisecrack belongs to Rose, who, when she finally relinquishes her death grip on Frank’s consciousness, delivers redemption as a punch line: “No one asked you to suffer. That was your idea.”

![]()